First Steps in Crafting a Novel

Deciding to write a novel is easy. You’ve made the decision. Now what?

There’s a lot of advice out there on how to start a novel. Most of it is conflicting, and very little of it takes into account the fact that every author is different. Your intuition and the things that motivate you to write are not the same as everyone else. As I discussed in Pantsing vs Plotting there is an entire spectrum of “types” of writers, and if your mind and heart are better suited to one style, then suggestions for the other style won’t be as useful for you.

So you’ll need to find your own path, and the only way to do that is through trial and error. That is not to say that you must go in completely blind. Finding your own path is easier if you have a map, after all. This article is meant to serve as your map.

The Idea

Some writers are blessed with having more ideas for novels than they have time to write. I am blessed to be in this category; I have over half a dozen books in my Fablehenge list, but only two of them have content. I find the question, “Where do I find ideas for a novel?” surprising. For me, the answer is, “everywhere”.

That’s not helpful for people who don’t also suffer from a glut of inspiration. Luckily, I have paid attention to where my ideas come from so I might be able to share them.

The first is Crazy vivid dreams. My dreams make as little sense as anyone else’s dreams, but if I wake up covered in sweat, I take it as a cue to try to remember as much of my dream as possible. I ignore the recurring ones like falling or my teeth falling out. Or the ubiquitous “forgetting my high school locker combo"", which is incredibly weird considering that I didn’t attend high school. But if my dream involves an unusual setting, or interesting sequence of actions, I usually find inspiration in it.

I don’t typically try to write down the entire dream. Dreams rarely make good stories; they are incoherent, disconnected, and random. And they involve an illogical number of lost teeth, forgotten passwords, and falls. I do have one story idea that came entirely from an unusually coherent dream, but for the most part, I just look at the dream for one or two interesting or unusual tidbits, and try to grow a new story from those pieces.

The second source of ideas for me is looking at the world and asking myself “what if?” questions. You have to be careful with these because a lot of “what if?” scenarios are social manifestos disguised as stories, and they don’t tend to have plots. Then again, some very famous stories were clearly inspired by “what if?” scenarios. 1984, Brave New World, and Left Hand of Darkness are just three examples. What if the world had perfect surveillance? What if everyone was genetically engineered to be happy in their life’s role? What if all the people were androgynous?

My first completed novel (unpublished) was based on the question, “What if all the humans are dead?” There are tons of post-apocalyptic stories where most of the humans are dead, and plenty of apocalyptic stories where the last of the humans are about to die (Philip K. Dick, Robert A. Heinlein, and Ray Bradbury covered this topic to death.) But I’d never seen one where all of the humans were dead. My main character is an AI archaeologist, studying the lost human race.

“What if?” scenarios come naturally to me, but you can train yourself to it. Jen will tell you that when I’m driving, I have a chronic habit of making up stories for the people in oncoming vehicles based on a fleeting glimpse of their facial expression. If you live in a less rural area than we, you can do the same thing walking down the street. Pick a random person, and work backwards. How did they get to that street on that day? The more you do this, the more ideas you’ll have. That particular person isn’t likely to feature in your next novel, but the skill you developed will.

You’re not me, though. If dreams and random inspiration just aren’t doing it for you, you might have to work harder at discovering an idea. One of the best suggestions I’ve heard is to try to find something unusual and combine it with something mundane. “Mundane” may not mean “normal” in this case. If you are writing in a fantasy genre, “mundane” might refer to many of the tropes, races, and plots common to that genre, while the “unusual” part would be throwing in something that is rarely used in fantasy. Similarly, the overarching plot of a cozy mystery is virtually set in stone; it is the characters and settings that bring a mystery to life.

Or maybe you’re going to mix genres. Brandon Sanderson has an entertaining “western fantasy” series, and Anne McCaffrey pioneered mixing science fiction and fantasy.

In my case, my career has been in software development, so I often find myself weaving coding-related themes into my stories. In a lot of settings, that coding aspect can be “unusual.” As a better example than I, Terry Pratchett did this masterfully in the satirical fantasy genre with “Hex” a sort of magical computer powered by ants.

If you’re still stuck for ideas, you’re going to have to do some writing without an idea, or rather, with a semi-random idea. For me this is a lot harder because I need to be excited about an idea to enjoy writing it. For folks that find idea generation difficult, though, it’s probably the actual writing that drives you; the idea isn’t what’s important to you.

One popular technique is to pick three to five objects and force yourself to incorporate them into a coherent story. It is commonly suggested to pick the first three things you set your eyes on as you look around your writing space. This might be good if you just sat down to write and are stumped, but taken too far, all your stories will be about things. I suggest going for a walk and picking a few interesting objects from your walk, or scanning through a list of headlines and finding objects in them.

I know Brandon Sanderson and Ursula Vernon have successfully published books written with this technique, but for the most part, I think it’s just a exercise, or, perhaps a springboard. If you end up with a compelling story that only includes one of the three objects after editing, you’ve still written a story.

You can also use the Internet as inspiration. There are entire subreddits and forums dedicated to writing prompts, as well as writing prompt generators. Older ones do the “select three to five random things” task for you while more recent incarnations use large language models. In fact, we intend to add an AI-driven writing prompt generator to Fablehenge, though the feature hasn’t been prioritized yet. Let us know if you’d like us to add this for you.

Who Are Your Characters?

It’s not mandatory (especially for discovery writers), but if you aren’t sure where you are going next, one good idea to capture the details of your characters. Some people like to draw up complex character sheets before they write their story (Fablehenge’s tagging system is perfect for this, and we have dozens of prompts to help decide what you want to learn about your character).

Others prefer to write the characters and then draft the character sheets as details come up. I fall into this camp; my characters are too dry if I try to pin them down without writing about them first. My general technique is to write a short story in the book’s universe that is not part of the book (Fablehenge Secret Scenes are ideal for this). As I write, I naturally start to describe the character and their quirks and reactions, and I learn what style of language they use. After I’ve written it, I dump all that information into a character tag so it’s easy to find when I’m writing about them in the real story. Then I generate a reference image, and if the AI spits out something that matches the mental picture I’ve developed for the character, I assume I have enough detail.

Even though I don’t personally write my character sheets up front, I recommend doing so for your first novel. It might work for you and it might not, but it’s important to try it so you know one way or the other. Even if you don’t flesh out the details, it is valuable to have a shallow list of key characters when you are looking for conflicts.

Finding a Plot

Once you have an idea, you need to build a plot around it. The key to a good story is understanding that it’s not just a sequence of random events in a cool setting with compelling characters. The events need to be tied together, they need to be compelling; they need to draw the reader through the story.

If this is your first time attempting to write a novel, I suggest starting with something much smaller: a summary of your novel in five to ten paragraphs.

Whether this works for you will depend somewhat on whether you are a discovery writer or an outliner. But if you don’t know which you are yet, writing a summary is a good way to find out. Even heavy-duty outlines often start by discovery writing a summary. And some discovery writers don’t want to have a whole summary because they don’t want to know the ending too early.

Your summary doesn’t have to cover the whole book in the same level of detail. Mine usually start out with very detailed paragraphs about the opening scenes, and then get less and less specific towards the end.

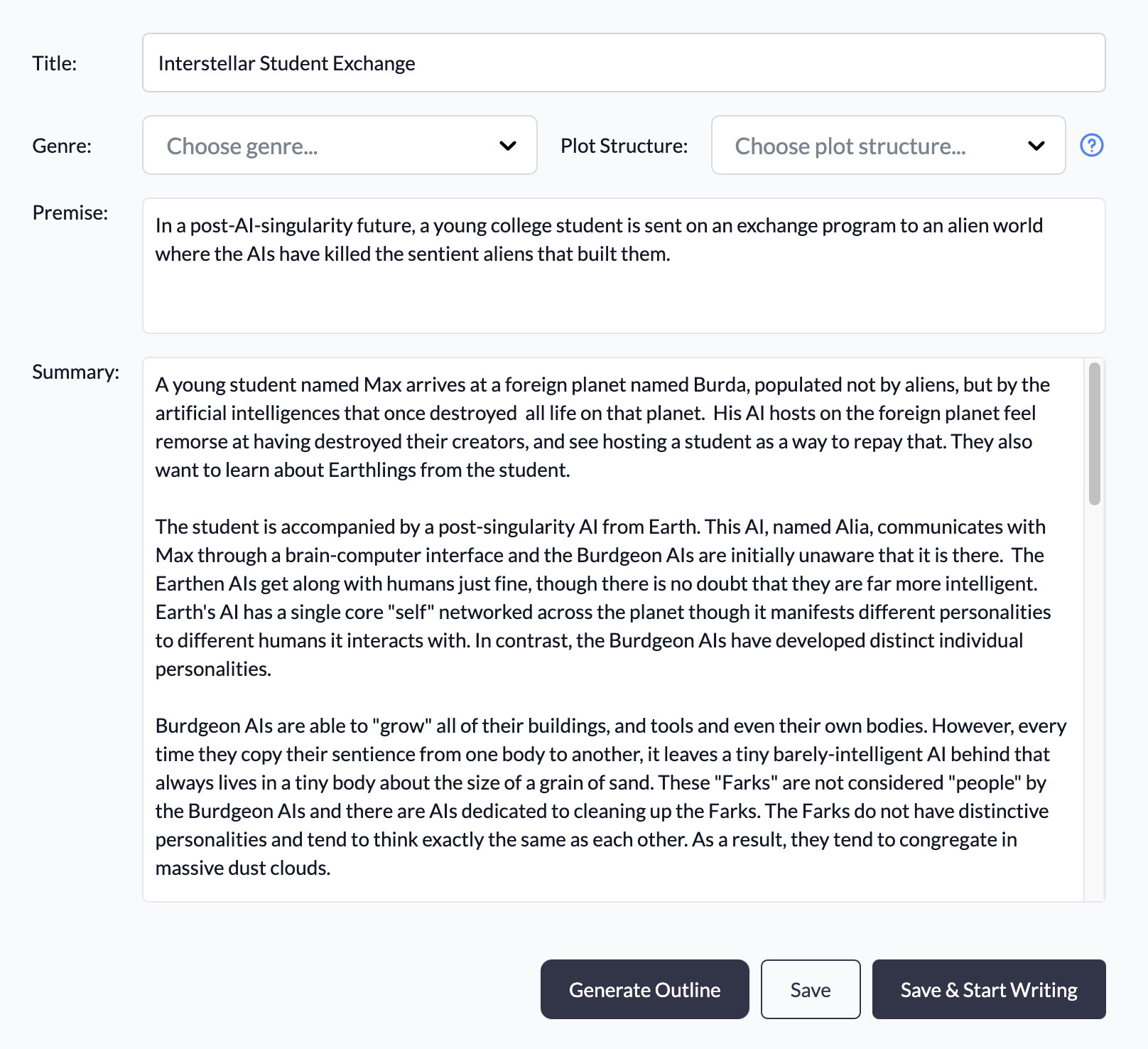

If you are using Fablehenge, we have an area to include your summary in the Book Overview tab:

For me, the summary is a living document. I update it as I write, partially to make it more detailed, but more often because the story is going in a completely different direction than I originally planned (This is probably less common for outliners).

The summary is optional. Not all authors find it useful. But if this is your first attempt at a novel, it is a good way to get from “I have an idea” (or a prompt), to “I have written something.” The first words you write will almost certainly not end up in the final book, but you can’t write the rest of the words until you’ve written the first ones. So get them out there!

The suggestion, “write a summary” isn’t necessarily enough to help you find your plot, but it gives you something tangible to build your plot around.

The truth is, there aren’t that many plots to go around. I’ve heard it said that there are only X different stories out there, where X is usually single digit number. So feel free to rip off the plot of your favourite book! If you have different settings and characters, nobody will know that’s where you started.

Consider mystery: If you base your story off any one Agatha Christie or Arthur Conan Doyle story, you’ll end up with pretty much the same plot, no matter what. But Hercule Poirot, Jane Marple, and Sherlock Holmes are all outrageously different characters, and each of those characters has dozens of completely different stories about them. All with the same plot.

If you search for “plot structure” or “story structure”, you’ll find lists of plot structures with a summary of the key elements. There are only about 10 named structures out there, depending how you cancel out duplicates. We’ll write a more detailed article on the plot structures available in Fablehenge at some point.

At this point, the important part is to think about your idea in the context of the various plot structures and see which ones suit it best. Then extend your summary with the ways that your key points interact with the chosen structure. If all goes well, you should find that your summary is starting to feel like a story, and if it goes really well, you’ll be excited about writing it!

For some ideas (especially those that revolve around a setting or character rather than an event or twist), it may not be obvious what story is there, even if you have picked a plot structure. The most important piece of advice I’ve received for these situations is to look for the conflicts. If it’s a setting-based idea, how is this interesting environment going to wreak havoc on the characters? If it is character based, what core competencies does the main character have, and how are you going to put the character in situations where those competencies are not helpful. What about the personalities of the various characters will cause a falling out?

Draft an Initial Outline

Since you don’t know whether or not you are a pantser or a plotter yet, the only way to find out is to draft an outline and see how it feels. I consider myself a very logical and organized person. When I write my non-fiction technical work, I always start with a detailed outline first thing. When I started writing a novel, I knew about the difference between discovery writers and outliners, but it never occurred to me to wonder which I was. I was obviously an outliner.

So it came as quite a surprise when my early attempts at writing fiction felt utterly uninspired. I finished writing the story for my outline, and then inspiration hit. The last third of my first novel was completely discovery written. And the reason I never tried to publish that novel is that the first two thirds feel inauthentic.

For my next attempt, I just started writing. I didn’t get very far because I had no idea where I was going. I gave up about 1/3 of the way into the novel. “Maybe I’m an outliner after all,” I told myself, and my third attempt was heavily planned and plotted. It was so boring to write.

That’s how I figured out that I like to have a short outline that covers the highest notes, but doesn’t go too deep. So that’s one strategy you can try if this situation sounds familiar to you.

Instinct tells me that folks who fall on the hardcore discovery writer end of the spectrum are unlikely to ask the question “How do I start?” The answer for them is obvious: start writing and see what happens! Since you asked yourself that question and are reading this post, I suggest that you start with an outline. Maybe it’s a detailed scene-by-scene outline or maybe it’s just a loose collection of points you want to hit as inspired by your summary.

If you’ve decided to try outlining, start with a very high level one. Basically, translate your summary to bullet points (Fablehenge Pro has a feature to do this automatically). Don’t try to hit every single scene in the first pass. Just hit the key turning points (inspired by the plot structure you’ve chosen), and write brief summary of what happens at each of them. Imagine that you are an omniscient watcher of the world that only checks in on their favourite characters every few days or weeks; whenever something important happens. Where are they now? Don’t worry about how they got there just yet; just hit the high points.

Personally, this is all the outline I want before I start writing, but you don’t know that about yourself yet. I advise trying to over-outline your first attempt. See just how far you can push it before it becomes boring, then a little more. You can always discard the outline and take your idea in a different direction.

If you are continuing with outlining, the next step is to try to fill in the gaps in your outline. Fablehenge’s drag and drop outline is great for this. When I attempted this, I usually found it helpful to “bisect” the major points I already had. If I know the characters are in this situation at one point and another situation later, where were they halfway between those two points? Now where were they halfway between that point and the one before it? The one after it?

Eventually, if you are discovering that you are an outliner, you will want to have a linear sequence of all the scenes in your novel. Or you might find that the outline isn’t doing much for you and you just want to start writing. But guess what, “How do I start?” was the question you came here for! If your summary and outline were enough to get you excited to start writing “real” content, you have your answer! Go write.

If not, maybe you need more detail before you are ready to start, and that’s great, too!

Scene Summaries

When I work on my early outline, some of the scenes are more vivid in my mind than others, and I fill in the summary with details of the scene as I craft the outline. Other scenes are more nebulous and I just give it a title and leave it as a placeholder in the outline. If that isn’t enough to get you ready to write, the next step is to ensure that all your scenes have a detailed summary. Exactly who is in the scene and where is it happening? (Fablehenge tagging is invaluable here.) What are they doing? Why are they doing it?

Most importantly, what is the purpose of this specific scene to your overall story? Are you trying to get the character from one location to another? Are you teaching the characters something? Are you foreshadowing some future event? If the scene isn’t actually doing something to propel the thought (and the reader) forward, cut it. Ideally, it’s doing more than one something.

For discovery writers, this kind of cutting happens much later in the process, but it seems you just might be an outliner, so you’ll feel more comfortable knowing that every scene exists for a reason and you know what that reason is.

If your scene summary feels too long or involved, split the scene into two or more scenes. If necessary, outline individual events in the scene. If you’ve gotten to the point where every sentence in the scene has an outline item, you’ve gone too far, but other than that, the only recommendation is to stop when you are comfortable.

Don’t Write the First Paragraph

Countless gigabytes have been invested on instructions for optimizing the first line, first paragraph, and first page of your story. This is the place where your reader decides whether or not they want to buy your book, after all, so it’s vital to get it right. Don’t worry about that yet. Those kinds of optimizations are one of the last things you’ll do in the final editing pass.

If you have an outline, and you’re still not sure how to “start writing”, I suggest starting before the first scene. Write a scene that you have no intention of placing in your final story. What did the main character have for breakfast that day and how did they feel about it? Or forget the main character altogether for a while and write a story about how their grandparents met.

If you are a discovery writer, you will almost certainly throw away the first paragraphs you write in your initial editing phase. If you are an outliner, there’s still a good chance you’ll be tossing the initial words. So it doesn’t matter what you write. Just get those irrelevant words out as quickly as possible.

Then pick a scene other than the first scene from your outline and write it. Nobody ever said you had to write your scenes in order. Pick the scene that is clearest in your mind. If you are still feeling unsure how to start, write the scene with the intention and expectation that you will throw it away. Sometimes it’s easier to write if you’re writing for practice than for an imaginary audience. At this point, the most important thing is to finish writing the scene. Don’t worry about all the things you’ve been told to worry about, including spelling, tone, voice, grammar, sentence structure, and purple prose. That’s all for the editing phase. We aren’t editing yet, we’re wondering how to start. It is so much more valuable to write poorly now than to write perfectly later.

Analyze The Scene you Wrote

Before continuing, take a look at the scene you just wrote and discover what point of view, tone, voice, and verb tense you intuitively chose to write it. Before you write anything else, make a conscious decision about what you want those things to be, especially the point of view and verb tense. Any of those things can be changed later, and it’s totally fine to accidentally switch verb tenses and clean it up in post, but it’ll save you a lot of fiddly work if most of you writing is already in the point of view and tense you ultimately settle on.

Write Another Scene

Any scene. Pick a scene! It can be the scene immediately after the one you just finished, or it can be the arbitrary scene that is clearest in your head. It can be the first scene if you want. You may be the kind of person who prefers to write in order from beginning to end. That’s great; now you know. The main reason I suggested starting out of order (other than bypassing the “OMG the first scene must be perfect” mental block) is that you need to know what it feels like for you when you write out of order.

And That’s It

Congratulations! You have started writing. There’s still a lot of work ahead of you to complete your first draft. Once you’ve done that work, you’ll have to start revisions and editing, which is a new skill set and also a ton of work. But the details of those tasks are best left for a future post. The main purpose of this one was to get you started.

Now that you’ve started, you are hopefully learning more about what kind of writer you are. The strategy I’ve given to get started might not work for you at all. That wasn’t the point; this method of outlining doesn’t even work for me! The point was to give you a strategy to try so that you can evaluate it.

So that is your final task: evaluate it. Now that you’ve started your story, which of the techniques you tried worked for you? Which ones didn’t work, and how could you tweak them to better suit your personal drive? Being an author (or any creative, really) requires a tremendous amount of self-awareness. You need to know how to find your muse at a moment’s notice; don’t sit around and wait for it to come to you.